Nothing can grow near Eagle Rock, they said. These were the days when the railroad was king, before the windstorm and the strike forced the town to change its name and pivot toward agriculture in a last-ditch attempt to save the economy. There were no farmers of any scale yet. There couldn’t be, because there was no dependable water other than the Snake.

So when Charles Tautphaus rolled up, bought a square mile south of town, and told the locals his plan, the disbelief was understandable. Besides, he was unusual, they said. Not because of his unpronounceable name or his background—an immigrant like everyone else in Eagle Rock—but because he seemed so sure of himself, so preoccupied with his own thoughts that he paid little attention to the townsfolk. And there was that vision of his, a picture in his mind of a lush lake, trees, orchards and flowers. Blue and green. If you wanted that life, why come here?

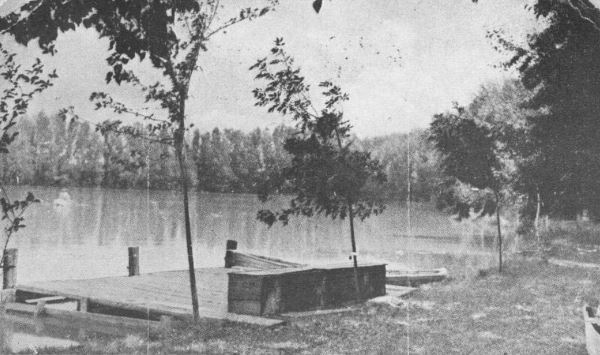

In 1886, the family moved in and set to work. Charles, his wife Sarah, and their five daughters ranging from 4 to 16 all pitched in alongside workhorses and equipment and dug a lakebed. This would be the focal point of the estate—a six-acre oasis in the desert. Now for the water itself. Tautphaus tried first to dig a canal from Sand Creek, several miles away, until recognizing that it wasn’t a dependable water source. The Snake, then. Early the next spring, his crew began digging, and blasting with sledgehammers, from a spot eight miles above Eagle Rock. His “Idaho Canal” had reached the lake by 1890. Then to provide an outlet for the lake, they kept going. The waterway turned 55 square miles of wasteland green, transforming the valley. Tautphaus, already rich, became richer. He and his family planted trees along both sides of their long driveway, which curved past the lake, over a bridge, and up to their stately home, alongside a stable and a smaller lake of clear water for stock, geese and ducks. Charles’s picture was complete.

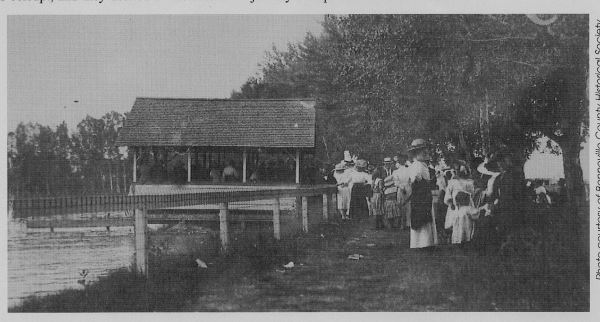

Tautphaus Park, as it became known, attracted day-trippers and tourists from afar to picnic, boat and swim at this oasis in the desert. In the winter there was even ice skating.

Tautphaus Park, as it became known, attracted day-trippers and tourists from afar to picnic, boat and swim at this oasis in the desert. In the winter there was even ice skating.

He had bested nature. And then, dream realized, he left to pursue other conquests: gold mining in the Yukon, freighting in Nevada. He died there suddenly, in Tonopah, in 1906. Three years later, Sarah sold the land to the Idaho Falls Boosters Club, who transferred it to the Bonneville County Fair Association, who installed fairgrounds, a racetrack and a grandstand near the lake. A few years later, as Reno Park, it hosted the first War Bonnet Roundups. The city bought back the land in 1934, opened a zoo the next year, and called the whole thing City Park before locals petitioned to restore its original, unpronounceable name.

In 1947, after a spate of drownings, Charles Tautphaus’s lake was emptied, and a picnic shelter and “sunken” baseball diamond put in its place, with a brand-new “kiddie park” called Funland opening nearby. Now, the park’s only water is his utilitarian Idaho Canal, pushing softly past his grave, the old lake, Funland and the zoo, and on to homes and farms southward.

His picture of an oasis in the desert is gone now. Thanks to him, so is the desert.

Research for this story was contributed by Carrie Anderson Athay, Museum of Idaho.

Click here to read more of the November issue of Idaho Falls Magazine.